Lisa wants to learn the total mass of water transported by the Agulhas Current. If she can glean its velocity, she can calculate its mass transport. But this is easier said than done, because the current wobbles in direction, sometimes pressed right up against the shore, other times meandering offshore; and it varies in velocity on short timescales and long. Therefore, only velocity measurements over a protracted period can reveal the true behavior of the current, and that's where the moorings come in.

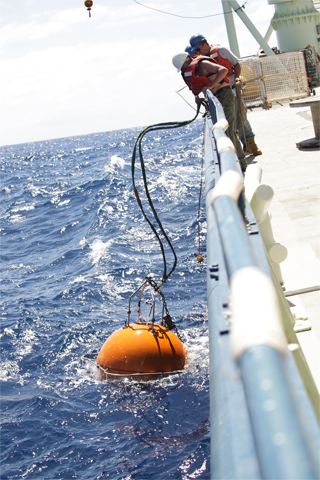

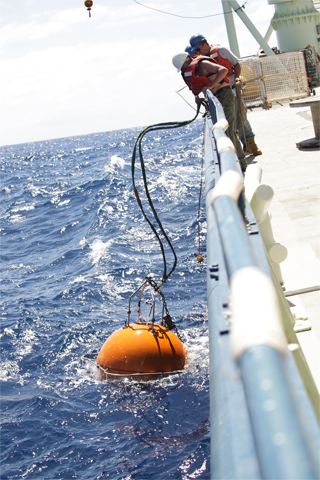

Picture the structure: a wire maybe three kilometers long suspended vertically between a two-ton anchor and a 1,500-pound foam float set near, but not on, the surface. Onto this wire, Chief Scientist Lisa and her technicians Robert and Mark have strung a series of current meters. Every twenty minutes, for the last three years the meters have recorded and stored velocity measurements. And that's the major advantage of the moorings: they can remain in the water for long periods, thereby resolving the constant, inherent variability in ocean-current behavior to deliver a mean.

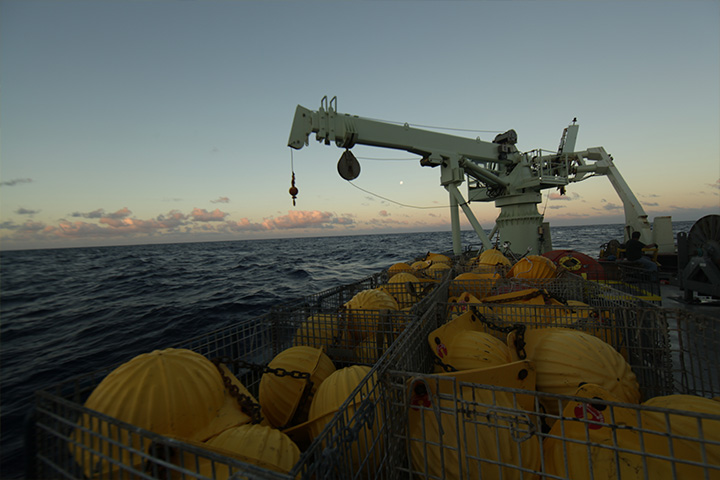

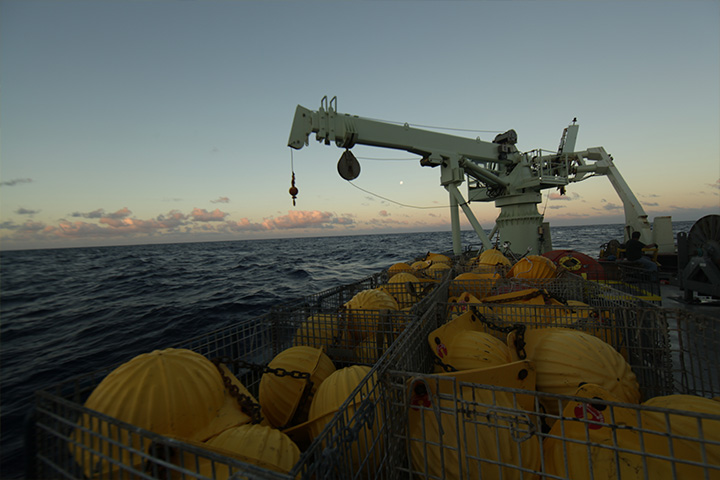

In the austral autumn of 2010, we planted seven full-depth moorings, and then in the summer of 2011, we came back out here to pull the moorings, collect their data and change batteries, and then redeploy them (see that year's website for an explanation and video). Now, 2012, we're recovering and taking them ashore, and that will conclude the at-sea portion of the Agulhas Current Timeseries. But that doesn't mean that the project is finished. All that data still needs to be parsed and analyzed, conclusions drawn. And then there is that all-important final step in the process: to publish the findings in technical journals. It is by that route that scientific knowledge advances.

Among the fascinating aspects of this work to me is the creative technical solutions people have devised to address the unique difficulties of measuring an ocean. Here's one. Mark designs the moorings such that the big top float remains 100 meters beneath the surface to protect them from heavy seas, fishing trawls, and passing ships. So how do you retrieve the moorings? By means of the acoustic release. It's a cylinder full of sound receivers with a stout set of jaws gripping the anchor. When the time comes to retrieve the mooring to collect its stored data and change batteries, a technician "talks" to the release in an acoustic code from a portable computer called the "deck box." The release responds in code, saying essentially, I'm awake and ready for instructions. The next code tells it to let go. The jaws that connect it to the anchor open, and the mooring - minus the anchor - floats to the surface to be retrieved and brought aboard. At least you hope it does. It doesn't always. And that's why they say, "If you can't afford to lose it, don't put it in the water."