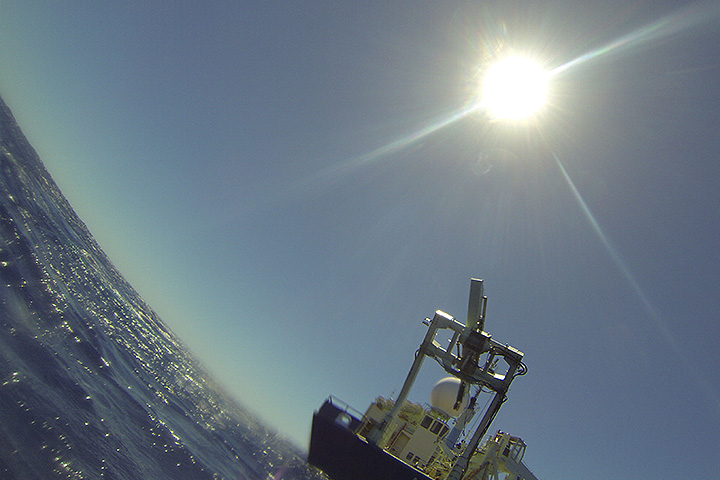

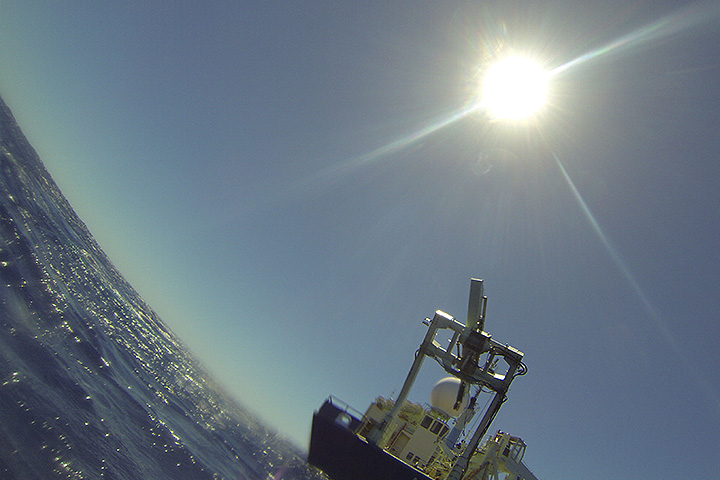

This fine old lady has traveled to the ends of the Earth: to the Southern Ocean near Antarctica, beyond 80° North latitude, and all seas in between. By 2005 she'd logged one million nautical miles in the service of ocean science. That's comparable to four circumnavigations of Earth at the equator or one trip from here to the moon. She's the ship that found the Titanic, but she's done much more important work for scientists seeking to understand how the ocean works. I've had the pleasure to participate in two oceanographic expeditions aboard Knorr in the Arctic and, now, my second, with Chief Scientist Lisa Beal and Captain Kent Sheasley, in the Indian Ocean. I, for one among many, have fallen in love with her.

Owned by the U.S. Navy and known officially as an Auxiliary General-Purpose Oceanographic Research vessel, she's operated, manned, and scheduled by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Her keel was laid in 1967 in Bay City, Michigan, where she was christened R/V Knorr after Ernest Knorr, the Navy's pioneering 19th-century cartographer; she slipped down the ways at the Defoe Shipbuilding yard two years later and proceeded to log an abiding list of impressive accomplishments.

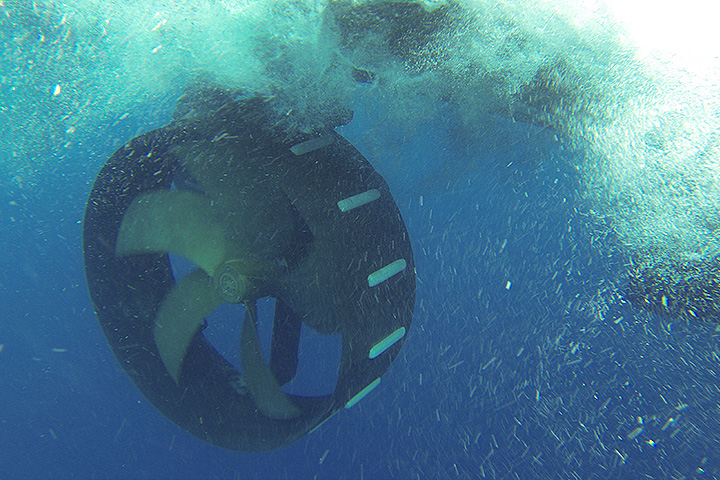

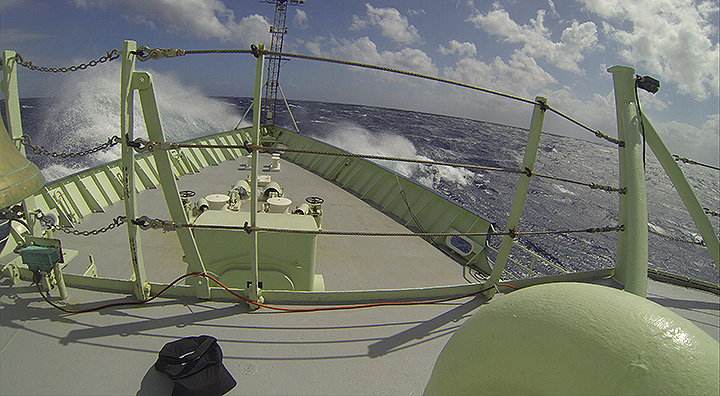

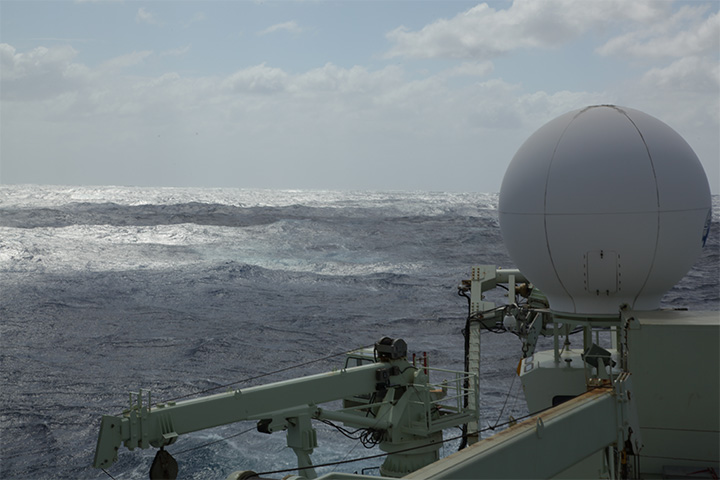

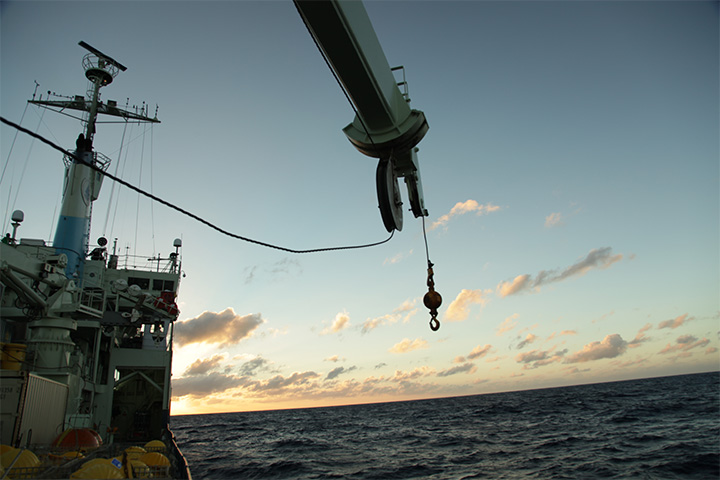

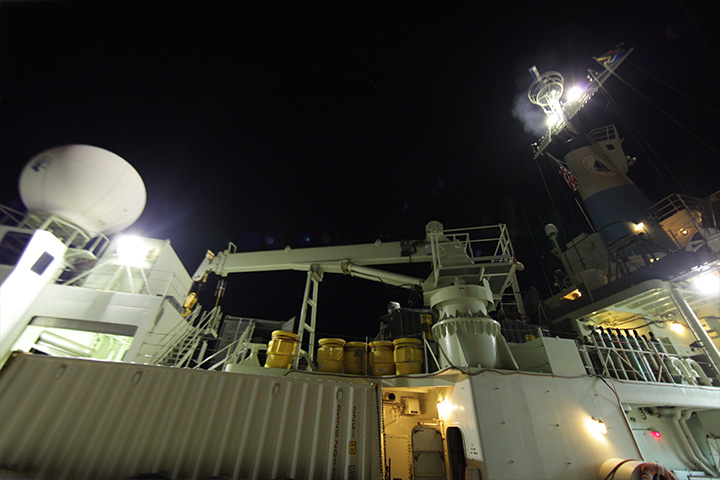

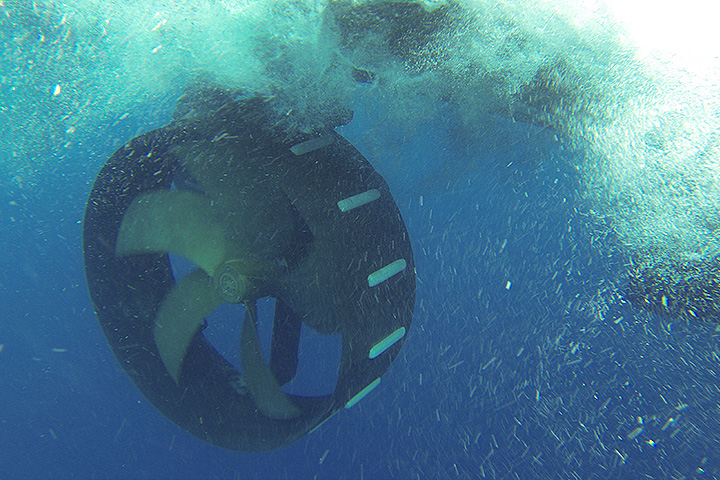

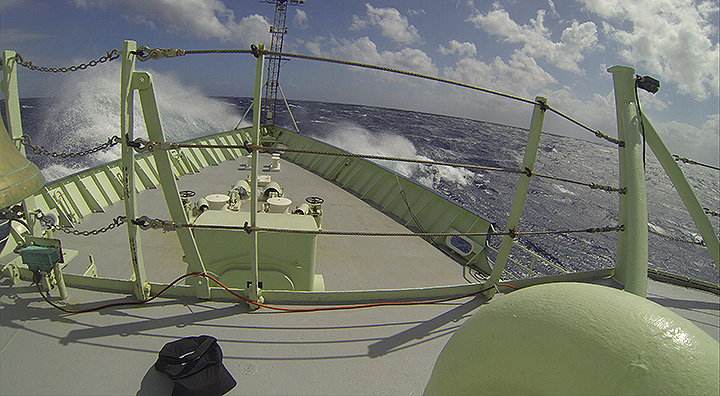

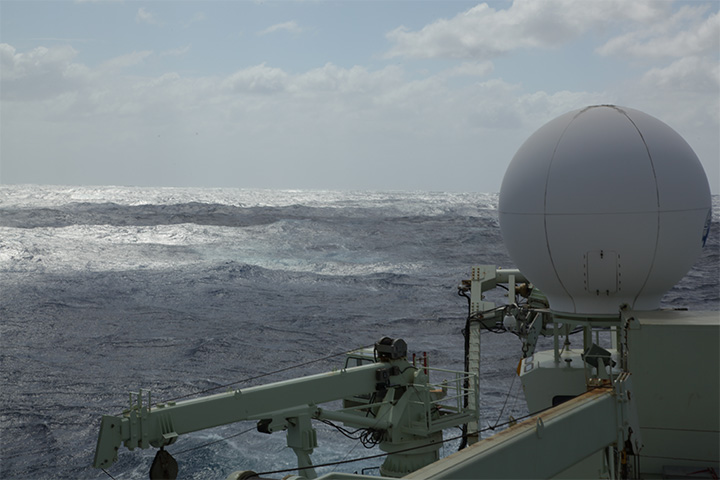

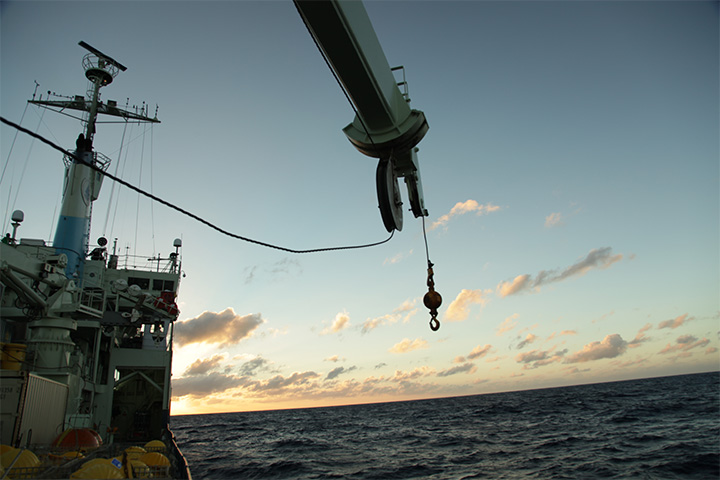

Most commercial ships, tankers, car carriers, freighters are built for a single purpose and most spend their lives steaming in straight lines between one port and another. However, ocean research is not singular. Knorr needs to be uniquely versatile, to serve the geologist who wants to drill deep bottom cores, the biologist gathering plankton, and the physical oceanographer who wants to lay moorings across a mean body of water such as the Agulhas Current. Knorr must routinely perform maneuvers no commercial ship-driver dreams of. She stops repeatedly in the middle of the ocean, even while a half-gale whips across her decks and holds that position for as long as it takes to deploy and retrieve all manner of measuring devices. This requires a specialized propulsion system in the form of "thrusters," as opposed to a straight-drive propeller system. Two thrusters in the stern and one in the bow, each can rotate ("azimuth") 360° to direct thrust in any and all directions. She can spin in her own length, walk sideways, or not move more than one meter in any direction. This of course demands equally specialized ship-handling skills and related deck work. When I first met Knorr several cruises ago, I was deeply impressed not only by that skill but by the confident informality with which it was being performed.

When I grew used to it, I began to assume that the high level of skill (and style) aboard Knorr was typical of all ocean-class research vessels. Well, it's not, I subsequently learned.

Throughout history ships and sea-boats have evoked strong, romantic emotion among their crews, who travel over big waters in utter isolation, where their lives depend on their shipmates' competence and their vessel's ability to withstand the ocean's violence. It's no coincidence, then, that crews come to think of their ships as living things. In the days of sail, going to sea left a death-like absence at home.

Maybe the sailor would return, maybe not. That isolation is less complete today (we have satellite communications, e-mail and Internet connections), but the feeling that she is alive abides nonetheless. It's not hip to speak these things out loud, and some of us might bury raw emotion beneath a quip or ironic joke, but it's clear to see that the people aboard love this ship. I do, too, and I'm only a sometime traveler.

I can't help feeling these things and speaking them now because there's an element of melancholy to the Knorr story. Her working life is approaching its end. Her replacement, the Neil Armstrong, is now abuilding in Anacortes, Washington; one hears two years, maybe three. Her captain and crew, who have nursed the aging lady over all Earth's oceans, grow quiet, pensive when the subject of her end arises.

They don't really want to talk about it. But all life, that of ships and people, is ultimately replaced by the new, and the crew is cautiously excited by a fresh ship for the future. But I don't really want to talk further about her end, so here are some dry-eyed nautical particulars:

Length: 279 feet (85m)

Draft: 16.5 ft. (5m); Bow thruster lowered: 23 ft. (7m)

Beam: 46 ft. (14m)

Gross weight: 2,518 tons

Range: 12,000 nautical miles

Speed: 11.0 knots cruising

Endurance: 60 days

Fuel capacity: 160,500 gallons

Propulsion: two diesel-electric stern thrusters, 1,500 SHP each

Bow thruster: retractable azimuthing, 900 SHP

Crew: 22

Technicians: 2

Science party: 32